|

We are very interested in any written or photographic history pertaining

to the island. We will update this website with appropriate information and photographs that you submit to us. Please contact

us if you have anything that you believe would be of interest. What

follows is information/pictures we have gathered to date.

History of Peche Island:

The Curse of Peche

Island

By Elaine

Weeks

The

little island lies just off shore in the Detroit River about two kilometres east of Belle Isle. Possibly you’ve noticed

its calming greenness as you hurry to work along Riverside Drive and wondered what’s over there. Perhaps you motored

over on your boat for a picnic and pondered the picturesque cement bridge. Older readers may remember when the island was

supposed to be developed into everything from a swanky housing development to an amusement park and wonder why all these plans

fell through.

According to descendants of the French family, which once settled the island for almost 100 years, there

is a good reason why Peche, or Peach Island, remains a virtual wilderness in the middle of an urban metropolis: it has a curse

on it.

The Native Legend

Before delving into the story

of the curse, it is worthwhile to reflect on the fascinating Native Canadian legend about how Peche Island was formed.

The

spirit of the Sand Mountains on the eastern coast of Lake Michigan had a beautiful daughter whom he feared would be stolen

away. To guard against this, he kept her floating in the lake inside a wooden box tethered to the shore.

The South,

North and West Winds battled over this maiden, throwing up a huge storm. The girl drifted away and washed up at the shore

of the Prophet, the Keeper of the Gates of the Lakes, at the outlet of Lake Huron. He was happy to find the beautiful castaway.

The Winds soon found her again and teamed up to destroy the Prophet’s lodge. The maiden, the box, parts of the

lodge and the Prophet were swept into the water and drifted through Lake St. Clair to the Detroit River. The remnants of the

box formed Belle Isle and the old Prophet was lodged further upstream forming Peche Island.

From

Legends of Detroit, Marie Watson Hamlin, 1884

The French Connection

On the earliest French maps of this region,

the island was named either Isle au Large, or Isle du Large. Possible meanings include “at a distance,” since

Peche Island is the farthest island upstream from Detroit before entering Lake St. Clair or “keep your distance,”

because of dangerous shallows on the north side.

The island was next called some variation of Peche Isle, including

Isle aux Pecheurs and Isle a la Peche, the French word for fish – the island was once used as a fishing station.

In

1789, what is now Ontario was divided into five administrative districts for the regulation of the land. The Board of the

Land Office for the Windsor region needed title to the island, which was mostly in the hands of the Indians in order to issue

land grants. A treaty with the Indians was accomplished in 1790 for lands in the western Ontario peninsula, but it excluded

Peche Island possibly because the Ottawas, Chipewas, Pottawa-tomies and Hurons who signed the treaty wished to retain the

island as a fishing ground.

Local businessmen possibly did not notice that Peche Island was not among the lands transferred

to the Crown and began petitioning for grants for the land. Alexis Maisonville was among them and it seems that he eventually

obtained some sort of title to the island and it even became known as Maisonville’s Island for a time.

Perhaps

the first permanent residents of the island were a French Canadian family named Laforet dit Teno. Evidence suggests that the

family moved to the island somewhere between 1800 and 1812 and possibly earlier – an entry in surveyor John A. Wilkinson’s

notebook for December 27, 1834 says the family had been living on the island for 34 years.

Irvin Hansen Dit Laforet,

a descendant, believes the family settled the island even earlier. In his article, “Peche Island: Occupancy and Change

of Ownership 1780-1882” he describes how Jean Baptiste Laforest was granted the island in 1780 for his service in the

British military as a guide and interpreter and for his family’s steadfast support of the Crown. (No deed was ever found,

however, nor was there any evidence of a grant recorded in the land office.)

Jean moved to the island with his wife

and his five-year-old son Charles. Jean built a homestead to verify his claim and passed the title onto Charles. In January

1781, Jean Mary Laforest was the first Laforest to be born on Peche Island. They had seven other children.

Apparently,

they shared the island with a group of local natives who occupied the western portion, keeping the eastern side for themselves.

According to Laforest family legend, Jean bartered with the natives to gain ownership of the island, closing the deal with

the exchange of some livestock. The Laforest family lived on the island confident of their ownership for almost 100 years.

By

1834, Charles and Oliver Laforet (the ‘s’ had been dropped by this time) maintained their large families on the

island. At that time about 25 acres had been fenced and were under cultivation. The settlers had constructed a house and a

barn, but there is no further information about their petition for a grant to the island.

In 1857, Peche Island was

finally transferred to the Crown by the Chippewa Indians, but there was no great rush to acquire grants perhaps because local

people believed that the island legally belonged to the Laforet family.

In 1868, someone did attempt to purchase it,

but because of the belief that it belonged to the Laforet family, no further action was taken.

“They and their

ancestors having been in possession for a long series of years, and having always regarded the place as their home, and considered

that they would be awarded at least squatters’ privileges in respect of the said Island. …the island may if sold,

be sold to the said Laforet or Teno family, provided they are willing and able to pay a fair price therefor.”

Essex County Council, Minutes, June 1868 - June 1873

The last Laforets on the island were

Leon (Leo) Laforest and his wife Rosalie Drouillard.

Leo was the grandson of Jean Baptiste and

had been born on the island in 1819. He and Rosalie, who had been born on Walpole Island and was the daughter of a Native

interpreter, had 12 children, the last being born in 1880.

They raised livestock, grew crops and engaged in commercial

fishing. Rosalie supplemented their income by weaving straw hats and selling them in Detroit.

When a deed for the land

could not be found, Leon staked out four acres in 1867 when it became part of Canada. He paid taxes on this property until

he died in 1882.

In 1870, Benjamin and Damase Laforest, cousins of Leon had entered into an agreement with a local

Windsor businessman named William G. Hall concerning commercial fishing. Benjamin filed a quit claim deed at the local township

office giving him squatter’s rights.

Many years later, an affidavit confirmed that Leon LaForest had agreed

orally to the commercial fishing contract, but he had never signed his name to anything. Hall applied for a land patent of

106 acres in 1870, which included the whole island except for Leo’s four acres. Hall eventually received title to the

island, minus the four acres for a payment of $2900 to the Crown.

After Hall’s death in 1882, his executor advertised

that Hall’s estate would sell the island, with fishing privileges and this sale raised the question of title.

Benjamin

Laforet (r.) was involved in a lawsuit with

Hiram Walker over land on the island

Hiram Walker’s sons purchased the property

from the Hall estate on July 30, 1883, as a summer home for their father. Benjamin Laforet filed a claim on the 1st of August

stating that he and his brother Damase had a one-third interest in a certain parcel of land that was described in the patent

from the Crown to Hall.

The case was settled and the Hall Estate was authorized by the Supreme Court of Canada to give

the Laforets a one-third share of the $7000 that Walker’s sons paid the estate.

Leo Laforet died on September

26 of that year. According to the Laforet descendants, a group of Walker’s men forced their way into Rosalie’s

home and made her and the oldest boys sign the deed over to the Walkers. In Laforet’s article, he writes, “They

[Walker’s men] threw $300 on the table and told Rosalie to be out by spring of 1883.”

That winter, while

Rosalie and her family were away in Detroit on business, someone came onto their property and ruined the winter stores. Because

Rosalie was knowledgeable in the ways of the Natives, they were able to survive until spring.

When it was time to leave,

Rosalie got down on her knees and cursed the Walkers and the island. “No one will ever do anything with the island!”

were her apparent words.

Walker’s Folly?

Despite his sons’ hopes that he would

use the island as a retirement spot, Hiram Walker occupied himself for many years attempting to develop it. For five years,

he had canals dug to allow boats to bring in supplies and to ensure the flow of fresh water through the island from Lake St.

Clair. Two yachts were purchased – the “Pastime” and the “Lurline” for travelling to the island

from Walker’s office and for cruises and parties on the river and lakes.

Walker built what has been described

as a 54-room or 40-room mansion. He planted hundreds of trees, put in an orchard, and built a green house to cultivate flowers.

He also put in a golf course, stables a carriage house and he installed a generator for electric lights.

It was widely

thought that this was no summer “home” for Walker but an attempt on his part to create a resort. The only problem

was, his intended market, the society people of Detroit, all went to nearby Belle Isle.

The Curse Takes Hold

Willis Walker, a lawyer who had handled the

purchase of the island, died soon afterwards at the tender age of 28.

Hiram did not enjoy the island for long. In June

of 1895, he transferred the land to his daughter Elizabeth Walker Buhl because of ill health. (Apparently, she was not a benevolent

Walker; legend has it that she did not let the locals pick the island’s abundant peach crop, as had been the case for

many years. She had them dumped into the river; they came in their boats to scoop them up.)

The

ruins of Hiram Walker's island mansion

Hiram was quite ill while he worked on his

Peche Island project, suffering a minor stroke before dying in 1899.

Edward Chandler Walker died relatively young

in 1915. Prohibition caused embarrassment for sons and grandsons who are American but operating a Canadian based distillery.

They didn’t want to be seen as bootleggers so they sold their father’s empire in 1926 only 60 years after he established

it.

Hiram Walker & Sons distillery was purchased by Toronto’s Cliff Hatch in 1926 ending the Walker dynasty.

The Walker family leaves Walkerville and abandon the town their father founded in 1858. Some remain in the Grosse Point area.

At the time of amalgamation with Windsor in 1935, no Walkers lived in Walkerville

How It Affects Island Development

Elizabeth Buhl sold the island to the Detroit

and Windsor Ferry Company in 1907. At that time, the president of the company, Walter E. Campbell stated that the island would

be made into “one of the finest island summer resorts in America,” and that “the big house…at the

upper end of the island…has 40 rooms and will be easily converted into a temporary pavilion at least” according

to the Detroit News, Nov. 11, 1907

Mr. Campbell apparently died in the home on the island that same year. The property

fell into a state of disrepair. In 1929, the house burned to the ground. Some say a huge lightning bolt hit it.

Needless

to say, nothing ever came of Campbell’s plans to create a park on the island. Although the island still legally belonged

to the Detroit, Belle Isle and Windsor Ferry Company and after 1939, to its successor the Bob-Lo Excursion Company, the island

remained deserted except for picnickers, young lovers and probably rumrunners during Prohibition in 1920s and 30s.

It

is believed that the Bob-Lo Company bought the island to deter development of another Bob-Lo Island (an island further down

the river near Amherstburg that had was developed as an amusement park until the latter part of the last century).

Peche

Island was so neglected that as late as 1955, the employee who guarded the island for the Bob-Lo Company spent his spare time

there fishing for sturgeon, trapping muskrats, and hunting ducks.

Despite vigorous efforts by local groups to have

the island purchased by some government agency for use as a park, the Bob-Lo Co. retained the island until 1956 when it was

sold to Peche Island Ltd. Their plans included filling the island’s water lot in to create a residential area. With

this aim in view, the remains of the Walker house were removed in 1957.

The scheme was abandoned that same year, reportedly

because of a lack of suitable landfill. Local rumour has it that the plan was in some way connected to the fact that Detroit

was short of space for a garbage dump.

Other proposals for the island followed quickly but nothing concrete happened

until 1962, when Detroit lawyer and investor E. J. Harris purchased it. His plan included dredging the canals and creating

a ski hill and protective islands. A few years later, Sirrah Ltd. purchased the island and its water lot. This despite strong

resistance by many Windsor delegations and groups who wished to see the island turned into a public park. Under the direction

of E. J. Harris, Sirrah planned and actually began work on an extremely elaborate park area for the island. He constructed

several buildings and sewage, hydro, water and telephone were connected to the mainland. The project operated for one season

with ferry boats from Dieppe Park and barges from Riverside. Due to financial difficulties and mismanagement, Sirrah declared

bankruptcy in 1969 also losing the 50-acre Greyhaven estate in Detroit.

R. C. Pruefer of Riverside Construction purchased

the island around that time with the view of developing it into a residential area or commercial recreation park that would

have included a marina but due to financial restrictions and other commitments, was forced to sell the island.

In 1971,

due to tremendous lobbying by various local conservationist groups, the island was purchased by Government Services with the

department of Lands and Forest as the managing agency. The island was also to be used by nature study students. The government

planned to spend a couple of million dollars on nature trails, picnic shelters, etc. but there were no funds. In 1974, the

property was designated a Provincial park for administrative and budget purposes.

Currently the island is a Windsor

municipal park, and the city has no immediate plans to develop it, apart from bathroom facilities. Other than part of the

foundation of Hiram Walker’s home, a bridge, some dried up canals and a piles of old bricks here and there, it is pretty

much the way it was before the Laforets were forced off the island.

Did Rosalie’s curse come true?

(With thanks to

Henry Shanfield)

|

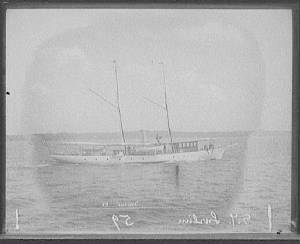

| The Lurline - Hiram Walker's yacht used to ferry family and friends to his Peche Island estate 1890 |

LURLINE'S DEMISE -

Other

names : none

Official no. : C90780

Type at loss : steam yacht and cargo vessel, wood

Build info : 1888, W. Lane,

Walkerville, Ont.

Specs : 79x16x8, 66gc 40nc

Date of loss : 1907, Oct 26

Place of loss : at Goderich, Ont.

Lake

: Huron

Type of loss : (storm)

Loss of life : ?

Carrying : ?

Detail : Wrecked while entering the harbor, total

loss. (collided with breakwater: Star)

August 2005 Update -

I spent an entire day exploring the island and found many contradictions

to the last paragraph with respect to the overall condition of the park.

The trails are very well groomed and marked. Picnic tables, barbeques,

fire pits are to be found everywhere along the trails. Washroom facilities and a main shelter are clean and appealing. The

beaches are clean and the waterways teeming with waterfoul - ducks, geese, blue herons were plentiful. The canals are not

dried up - I navigated most of them easily in a kayak although some areas are thick with floating weeds and lilly pads of

all colors - yellow, white, red. But naturally beautiful!

The only problems I could see were cans, bottles and even an

old tire floating in the canals, a couple of makeshift bridges that should be replaced and an obvious lack of visitors

to the island which is not surprising given the fact that there is no way to get to and from the island unless you own a boat.

Other than that, it's a beautiful, natural and peaceful oasis in the middle of an urban and industrial sprawl. Do the

citizens of Windsor have any idea of what they have here??? You'd have to drive north for a day to find such a natural wilderness.

| Click this CWS Logo for Species at Risk in Ontario |

|

|